Most modern bicycles use variations of a design called the dérailleur; literally, the de-railer, a device which forces the chain from one cog to the next in a very unsophisticated and crude manner. In engineering terms, it really shouldn’t work … but it does.

Modern dérailleurs use all manner of tooth profiles, chain design and indexing devices to enable this to happen as smoothly as possible.

But, just as changing gear on a manual gearbox car needs finesse and an understanding of the principles involved, compared to say, an automatic gearbox, changing gear using dérailleurs on a bicycle also requires a degree of involvement from the rider, more than just pushing the button and crunching on regardless.

Some modern bikes have up to 30 possible gear combinations – 3 at the front X 10 at the rear – but not all permutations are useful either because some combinations of front and rear cogs produce gear ratios which are very close to another or even identical, or are mechanically compromised. More about that later …

Changing Gear: The principle of the dérailleur depends on the chain moving forward through the gear change, so when changing gear, continue to pedal forward.

However, it’s really helpful to the change if pressure is taken off the pedals so that for the duration of the procedure the feet just spin until you sense the gear has engaged and take up the effort again.

There are occasions when this isn’t possible, but just assessing your gear needs ahead of the point where you have to change facilitates a smoother procedure. This particularly applies when you’re changing down to a lower gear, for example, on a hill, or changing to an easier gear just before coming to a halt.

The front dérailleur usually needs the most practise to use efficiently because the chain has to make such a large jump from one chainring to the next.

People often ask, “How do I know what gear I’m in?” or “How do I know if I’m in the right gear?”

The thing is, you don’t really need to know as long as you feel comfortable and can maintain a good pedal cadence and the drive runs smooth and sounds quiet. But there are some gear combinations to avoid.

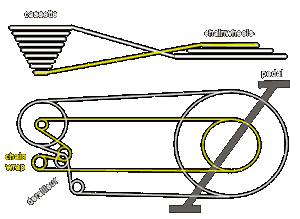

Cross-Chaining: The diagram shows the top view of a typical set up. I’ve indicated the chain line from the extremes of the chainwheel to the cassette.

Although exaggerated, it demonstrates the degree of deformation the chain has to cope with in those gears. This tends to cause the chain to track badly, run noisily and the dérailleur mechanisms to have to contend with excessive chain wrap, extension and tension.

In practice, try to restrict your gear choices as in this diagram; large chainwheel to outer range of sprockets, small chainwheel to inner sprockets.

Modern gear indexing systems control the movement of the dérailleurs, often to a tolerance of 0.1mm, less than 1/100th inch. One of the prime reasons for gears to go out of adjustment is cable stretch, particularly with new cables, so if you’ve recently bought a new bike, or installed a new cable, return to your LBS to have the adjustment done if you can’t do it yourself.

Another frequent cause of poor shifting can be a bent dérailleur hanger, the component which connects the rear mechanism to the frame.

If your hanger is bent you will need to visit your LBS where they will have an alignment device which can check and adjust the hanger. The hanger will need to be adjusted in three planes so it’s not really a job you can do at home.

But adjustment can also be affected by using excessive force, either through the gear changer or through the pedals while changing gear causing elements of the drive to distort or just go out of line, so learn to coordinate your changing/pedaling skills as outlined above.

A well adjusted gear mechanism will produce easy and smooth changes. However, it does need some input in terms of timing, sensitivity and skill from you, the rider.

If you’re seeking information on other topics click on any item in Halter’s Tag Cloud in the right hand column of this blog …

Alan – That British Bloke

My Bike

My Bike